Designing The New Age: The Art Of Andy Martin

Fast forward 40 years and a chance meeting in a Kent art gallery (recounted below), and Bill was revealed to in fact be a pseudonym for one Andy Martin, who after his brief entry into the nascent On-U Sound story, went onto enjoy a varied and interesting graphic design career. Around this time we also connected with Andy on social media and noticed that he was still making tons of amazing collage art with the same irreverent wit and DIY style as had been displayed all those years ago on the sleeve of the first On-U album.

In another cosmic coincidence, at the time we re-connected with Andy we were in the process of putting together reissues of the New Age Steppers albums, and intending to do an album of rarities and deep cuts, in the tradition of archival albums we’ve released in recent years such as the Return Of The Crocodile and Churchical Chant Of The Iyabinghi sets for African Head Charge, and Displaced Masters for Dub Syndicate. A few friendly exchanges soon turned into a commission to complete the art circle 40 years later and design a companion sleeve to ONULP1 for the Steppers rarities set Avant Gardening. We’re really happy with the work he’s done for this, and below we chat to Andy about his work with On-U Sound (then and now) and the rest of his fascinating career, from the late 1970s to the present day.

Finally, a personal note: like most people who work in music I started out as a fan, and as a teenager would spend every spare bit of money wangled from paper rounds and Saturday jobs on records, totally obsessed by and absorbed in music. I grew up in Leicester, which had quite decent secondhand record shops, but the ones in neighbouring Nottingham were even better, so every couple of months or so when I’d saved up enough I would take the train over there and spend a whole afternoon going through the racks at the different branches of Selectadisc on Market Street, trying to get the best bang for my very small buck. It’s hard to believe in these straitened times that an independent shop could have three sites in one street, but at that time Selectadisc had a shop for Dance 12″s + import Sub Pop 7″s at the bottom of the hill, a secondhand shop halfway up, and new records (over two jam-packed floors) at the top.

One Saturday in Nottingham I kept coming back to one record I’d seen on the wall of the secondhand shop with a super weird cover that caught my eye. In those pre-internet days, knowledge about esoteric sounds was hard to come by so I had to scan the sleeve for clues. I vaguely recognised the names of some of the people on the back cover as being from post-punk bands I’d read referenced in reviews in the music papers, but never actually heard, like The Raincoats, The Slits and The Pop Group. It was on a label called On-U Sound which again I’d heard of but never knowingly heard any of the music they’d released. It cost more money than I would usually pay for a record at that time but there was something about that cover drawing me in so after a long time pondering I handed over the cash and took it on the train back to Leicester. I put it on the record player as soon as I got home and I’ll be honest, did not get it at all. What was this? It started off with a reggae song, then some weird instrumentals, followed by a man howling over some industrial noise. The last track featured a woman talking about the heavy metal boys and the boys in blue not liking the look of you. It was deeply odd. But I kept coming back to it because I’d spent too much on it not to, and it slowly became one of my all time favourite records, and my introduction into the weird and wonderful world of On-U Sound. If you had told me back then that I’d get to work with the catalogue years later I’m sure I would have spontaneously combusted on the spot. So big up Andy for coming up with such eye-catching artwork and helping to pull me down the rabbit hole, and of course Sherwood for always working such magic at the controls.

Introduction and interview by Matthew Jones

Transcription and layout by Albert Carter Phillips & Jennifer Metcalf

All artwork by Andy Martin

The obvious place to start is just at the beginning. Where are you from, how did you get a start in what you do now?

I went to art college in Derby, and I did a year there, and all my mates kind of upped and left to go to London, so I did this first year of a graphic design course, and just thought ‘I’m out of here’ so I dropped out and came to London just on a whim really.

Do you have any regrets about dropping out of art school?

I don’t think I was cut out for it, and it was very provincial. At the time they were just churning out people to work in companies, there was a big printers called Bemrose who did all the Rolls Royce stuff, so you either went to work for them or British Rail. It was a really interesting time, 1976, but everywhere except Derby!

Then it was a series of happy accidents, I came to London and got a job painting corridors upstairs at The Rainbow Theatre, because I was squatting in Finsbury Park, just painting these endless corridors, because the guy who ran The Rainbow had a flat right at the top of the building, and through that there were all these rooms and all these funny little enterprises. There was one room full of girls making Hawaiian shirts, just a rag trade you know. There were loads of rooms and I think the guy who ran The Rainbow would just rent to anybody, so he filled it with all these people doing various, nefarious bits of work. One of whom I bumped into and she said ‘Oh, you do graphic design? My sister works for Felix Dennis’, and I had no idea who Felix Dennis was at the time, and she said ‘you should go down there and you’ll get a job’. So I just went along there and got an interview with this guy who sealed the deal with a swig from a Johnnie Walker bottle and said ‘start Monday’. I don’t know what I’d done to persuade him because I had absolutely no skills, I just had the gift of the gab.

Did you have a portfolio or anything?

I didn’t have one, at the time I was just collecting bits of graphics and stuff. Much later on I went for a job at Stiff Records in the art department, I had literally walked in with a carrier bag full of litter as a portfolio. I didn’t get the job, they asked how much I wanted and I said £100 a week and they just all laughed into their hands and I left. But anyway I got this job, Felix Dennis had a publishing company called Bunch Books, and at that time he had been publishing all the kind of San Francisco comics like Zap Comix and Robert Crumb stuff, and he’d done Oz Magazine of course. Oz had finished and he’d started getting into serious publishing with things like Which Bike and Hi-Fi magazine and Kung Fu poster magazines – a lot of poster magazines, he kind of cornered that market – and that’s where I cut my teeth, learning the basic studio skills.

What exactly were you doing on these magazines?

Paste-up: sticking bits of type down, putting it through a waxing machine, cutting it into very small pieces and building a page with it – including corrections which could end up often meaning stripping in full stops and commas, that kind of work. I was getting a design education in a sense, the use of all the materials and the means of production – big process cameras and stuff – I picked all that up quite quickly, but then it was at the height of punk rock, and I just lost the plot a bit really. Felix gave me £100 and a drawing board and told me to fuck off basically, which was good, I got sacked in a really good way, and it galvanised me and set me up, and then within no time at all I was getting more freelance work from Felix than I had been on his staff, so it worked out in a way, it was just the kick up the arse I needed.

So were you basically just working for yourself at that point?

Yeah picking up bits of work at other studios, there were lots of days at Time Out magazine, you’d do days in different studios, you’d pick up a couple of days here and a couple of days there doing layout and design. At that time there was a big split: City Limits got set up by the people who’d walked away from Time Out and there was a bit of a battle going on, and then Virgin had one called Event Magazine for a short time, and there was loads of work on those listings titles because they were weekly.

Then there was a big strike at IPC [magazine publishers] and the NME and Melody Maker were put out of action, and Felix Dennis being the smart cat he is, invented a music paper and turned it round in like ten days, he had one on the stands called New Music News which was pretty poor but it was a great opportunity to get in there and work in the field that you wanted to be in. It was around that time when I met Adrian at Felix’s. I think I was just visiting, dropping off some artwork for New Music News. I’d done a collage for The Mothmen, a band that Adrian was involved with.

We bumped into each other on the stairs and someone introduced me to Adrian and said ‘this is the guy that did that collage’ and Adrian said ‘Ah right, so you’re interested in doing something together?’, and that turned out to be the first New Age Steppers album. He gave me a tape of it, which I loved immediately, I just thought ‘this is the right stuff’ you know? And he seemed to be into the collage I’d done for The Mothmen because it was quite playful, it wasn’t righteous or anything, well you know the sleeve, it’s become legendary in it’s own lunchtime by now.

Did Adrian give you any brief?

No! He just gave me a tape. And I was actually living in Devon at the time – the Devon, Cornwall borders – playing in this band, so I was shooting up and down between there and London, doing a bit of work, bit of band, bit of work, bit of band, and I did the artwork in Devon. I was trying to speak to Adrian on the phone in a callbox with the pips going and it was chaos. I ended up putting it in the post back to him. Then I didn’t hear anything and I wasn’t sure how it had gone down. But then I got word back that, yeah, it was a goer. It was great. It was a real shot in the arm for me at the time as I was trying to get into image making, away from design work. It was the perfect gig, right at the start, and it kind of defined the way I worked from that point on really.

Have you done many other record sleeves?

No, I think it’s because I got established in print quite quickly, in editorial, and the music industry always seemed to be full of charlatans at the time. I remember I had a really hard time, I used to visit all the record labels regularly: I’d go to Island, I’d go to Polydor, I’d go everywhere – and it was always some guy with cowboy boots with his feet on the table, looking at you, talking to you as if you’d just dropped out of college, in one of those great big knitted cardigans with Peruvian patterns on, and a slashed-to-the-waste cowboy shirt. Horrible. I have done some sleeves, a few scattered through my career, often because I knew someone in a band who wanted something doing, but I’ve never gone and done any work with majors or record labels particularly.

Why did you choose to use the Bill Bell pseudonym rather than your real name?

Well that’s interesting isn’t it, because I was influenced by Barney Bubbles – everyone was – and I wonder now if that alliterative thing was something to do with that. I think I was having a giggle with it, it was like a reinvention in the punk days. Part of the deal was: anyone can do anything, and anyone could be anyone. So, having a pseudonym wasn’t a big deal, I used to see my pieces of work like singles… it’s hard to explain it now, but at the time they were like records. Physical things you’d built. So the whole persona went with that really, just dropping this stuff out. Loads of people had pseudonyms, the reason I had one in the first place was probably to do with signing on, and I was doing bits of work at the same time so I was nervous about all that.

How did you start working with the NME and doing work on the music papers?

There is a Barney [Bubbles] link there because I knew a girl called Caramel Crunch – because everybody had an alias, I was Bill Bell, everyone had alliterative aliases – but she knew Barney, she was working with Barney as an assistant occasionally. Caramel was also working at the NME and she used to get me to cover for her occasionally, so I used to go in there and do a bit in freelance mode, and I got to know people there. After a couple of years of that, and another art director, they offered me the gig. I kept turning it down, they asked me three times I think, and I was going pretty well on my own, and in the end I just thought the NME was somewhere I’d really wanted to work for years previously, and I just thought ‘go and do it, get it out your system’.

What kind of stuff were you doing for them?

Laying out the paper which was quite difficult at the time. I was used to actually physically sticking down a copy, but with the NME you had to draw paper layouts and some bod up in Northampton would do it for you on press day. So it wasn’t hands on and you can’t really design like that, it’s much more intuitive when you’re pasting it up, whereas when you’re doing paper indications and hoping someones gonna get it, it was like being a ventriloquist really. But the upside was all the special projects like the cassettes and the bits of promotion, and the covers – I didn’t do many covers, there was a constant fight there with who did the covers with the NME. For some reason the features editor got the gig of doing the covers most weeks.

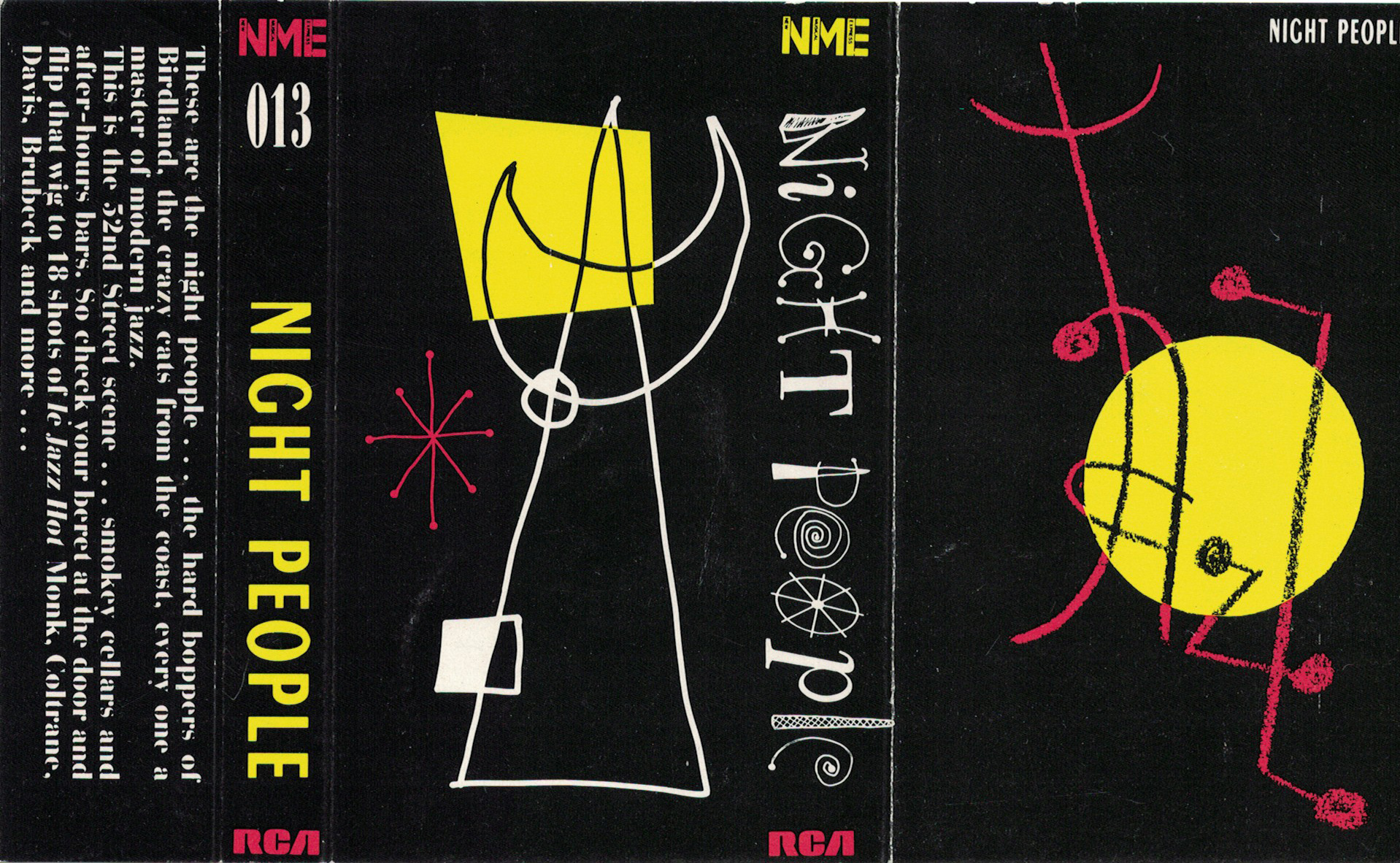

Do you remember which NME cassettes you did?

I did Little Imp, I did Night People, I designed a load of them but I got to actually illustrate the covers on some of them. Little Imp’s probably my favourite because it was a pastiche of the Ronson lighter fluid tin. It’s that thing where you play with the title and you get a whole package out of it.

And presumably working on a weekly newspaper, that can be quite stressful with deadlines and stuff?

Absolutely, it was murder, and some of the journalists had better reputations than others for delivering on time. There were people who’d deliver it handwritten on the day. There were different deadlines for different sections of the paper, and they’d be keeping the big story in the bag, well in advance, but then you’d have lots of stringers round the country doing live gig reviews, and little news stories to drop in – a multi layered festival of deadlines really.

And the early 80s would have been the peak of their circulation right?

Yeah, it was, after I left it started going down, go figure! It was fantastic. It was under the editorship of Neil Spencer, who doesn’t often get the props he should, he was great. He broadened the brief, it was a good time to be there: video was just kicking in, it was getting women in there, it was issue based, it was great. It was a real break from the old pale, stale, cock-rock, because even punk rock had that in it, it was a very male place.

Why did you leave the NME?

Well it’s a cycle, and I’d done three of them. There was more interesting stuff happening, I’d started to go to visit Italy and do a bit of studying – sort of – I got into doing bits of furniture design, and really thought I could have a go with that. You’re picking up bits of freelance work while you’re at the NME, so there’s lots of interesting things coming your way, and I just didn’t want to go into another round of it. One Christmas I just thought ‘I’ve done my last Christmas issue’, that’s the last time I do that. It was all very amicable, I was very happy to have spent some time there, but I had more interesting things to do than just do a paper every week, which included filling in the black squares of the crossword with a rotring pen.

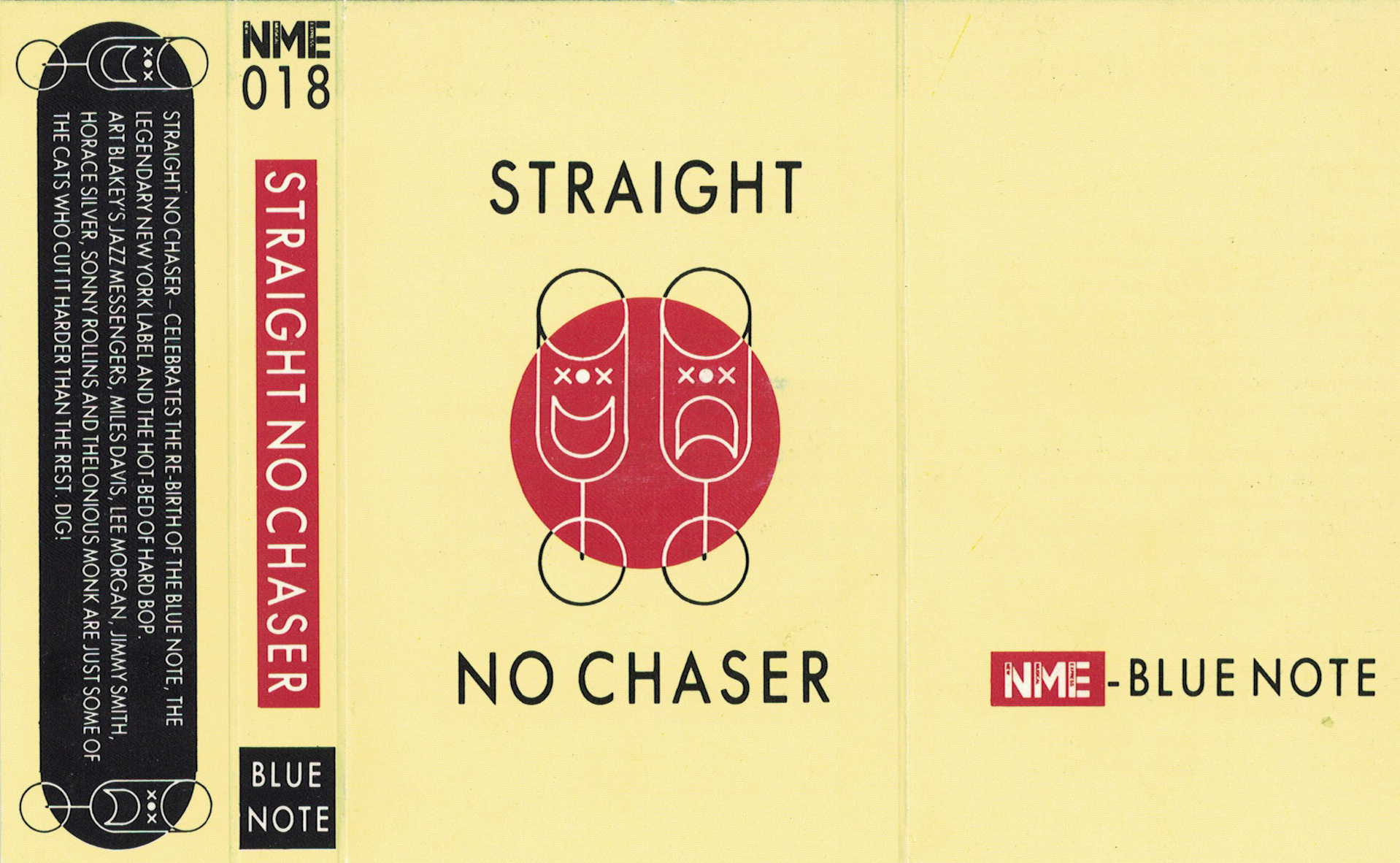

How did the Straight No Chaser thing come about?

I just helped them out really because Paul Bradshaw was an NME contributor but he was also a friend of the house I was living in – in fact he actually introduced me to my Mrs – and Kathryn Willgress his business partner was working in the same shared house, so I knew them and helped them out with the front covers for the first three or four issues. But then Swifty [Ian Swift] took it and made it really what it is today. Mine was just a little side aberration really. It was great because I was able to put these ideas in that I couldn’t get in the NME. I wanted blank covers with small iconic images on them occasionally and the sales guys would be like ‘It won’t show up in the newsagents, you can’t do that’, so I got sick of that really, the criteria of design, and Straight New Chaser was a great opportunity to just go ‘let’s have it upsidedown, fuck it’.

Have you ever just published something just for your own pleasure?

For the last 10 years or so I’ve had an ongoing collaboration with poet and broadcaster Ian Macmillan. We’ve published a book and we’ve also taken advantage of the online social media thing. We have an ongoing project on Twitter, every couple of days where we do a collaborative piece. Instagram has been an amazing thing in terms of getting your ideas out. I mean, probably we’ve had more hits on a picture of the book, than people bought the book.

I guess it’s like instant publishing.

Yeah, and I’m more interested, to be perfectly honest with you, in ideas and where they go, rather than coining it, because I think in order to coin it, the idea is the first casualty. So in those terms of getting ideas out to as many people as possible, social media has been really amazing. You get feedback, spurring you on, changing the way you look at your own work. It’s really dynamic.

What’s the difference in your approach between stuff you do for yourself, and for a client?

Well it’s funny because this lockdown my illustration and editorial work was slowing down. Now there’s a number of reasons why that’d be: print is changing, a new generation coming through, ideas moved along… I think I’m still up for the fight with my image making though, I’m not giving up.

I used to really enjoy working with the Americans, because I did a lot of work in the States, I had an agent that had an office in London and in New York. Once you get used to the way they work where: once you’re on board, they’re not letting you go – and it can be midnight and you’re still there – once you get into that way of working they’re brilliant. They’re very thorough and clear. So it’s usually a joy to be briefed by them. They’re straight and they’ve thought the brief through before they’ve given it you, and they’ve given it to you because they think you’re the guy to do it. And that’s really enjoyable.

That’s come right at the end of a career that’s often been tortured with people who didn’t know what they wanted and didn’t like what they saw when you tried to guess what it was when you showed them something. There’s a big difference in those two ways of working. So what’s happening now is I’m in complete control of the imagery I do and what I play with. There’s no money coming off of it but my work feels amazing. I’m really enjoying flying with it. You can demonstrate what you want to do, rather than the work you know you’ve already done.

Do you have set hours that you try to do stuff in, or do you just have to get something down when the idea comes to you?

It’s all that and the rest. I’m in here every day, in the studio. Some days I’ll do two hours of an idea I’ve had in the middle of the night and then play the guitar for a bit, and then go for a walk. It’s a really broken work day but each day the sections seem to fall into a similar pattern. Some days I really have to make myself stop and get out of here because I’m hungry but i’ve still got an idea on the go. I’ve still got this kind of enthusiasm for it, which is great. A lot of people who have worked this long haven’t got that. I’m lucky.

What are some of your favourite commissioned projects you’ve done?

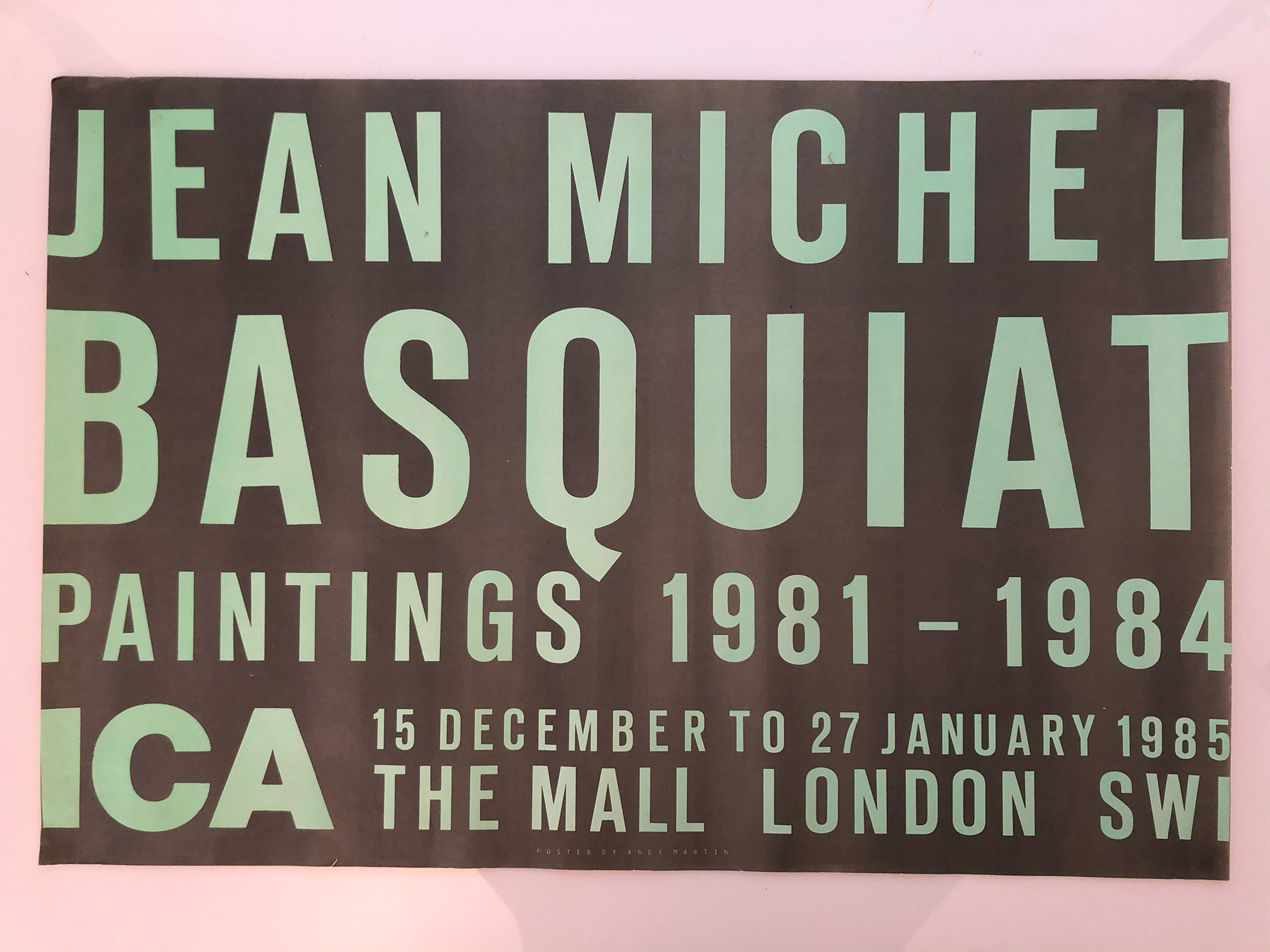

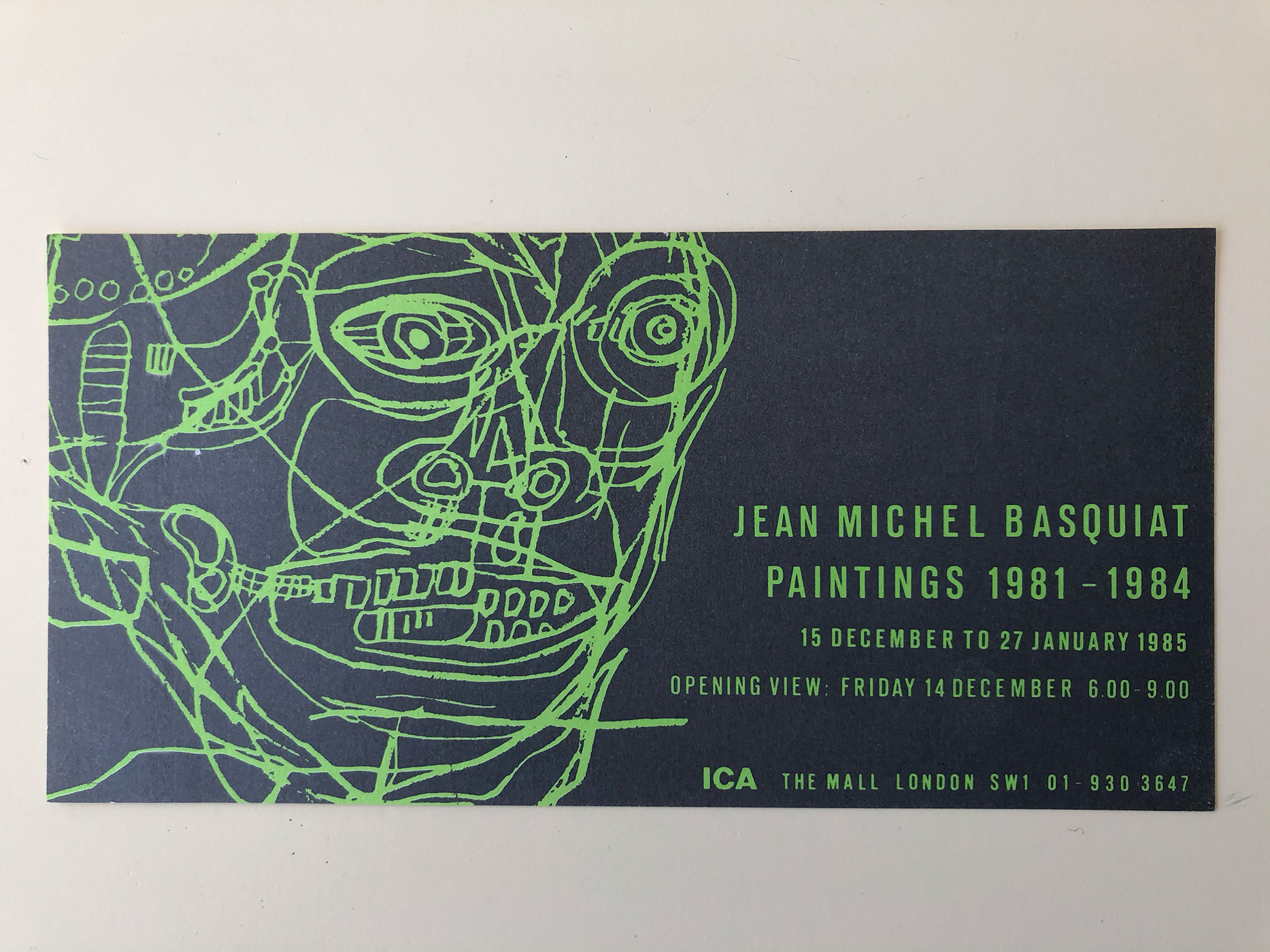

The first thing I did when I left NME was set up a studio. I was hanging out at the ICA because it was a really good place to hang out. A bunch of mates used to go there all the time – it was like the NME canteen really. And I got to know some people there and I picked up a gig for the first Jean-Michel Basquiat exhibition in the UK. It was just a dream job and it fell in my lap. Because his work is so amazing – and I don’t know what made me think of it – but I just kept all that off the poster and did a typographic one. It’s interesting looking back now because that colour palette I used and that typeface became a standard set pattern for art gallery promotion. I used to get Art Forum magazine and lots of NY galleries all of a sudden had this minty green on a grey background with double spaced type, and I was like: ‘I did that’! So that was kind of a little personal achievement I felt. I might have been wrong, it might have been the zeitgeist and it was happening anyway, but that was a great job.

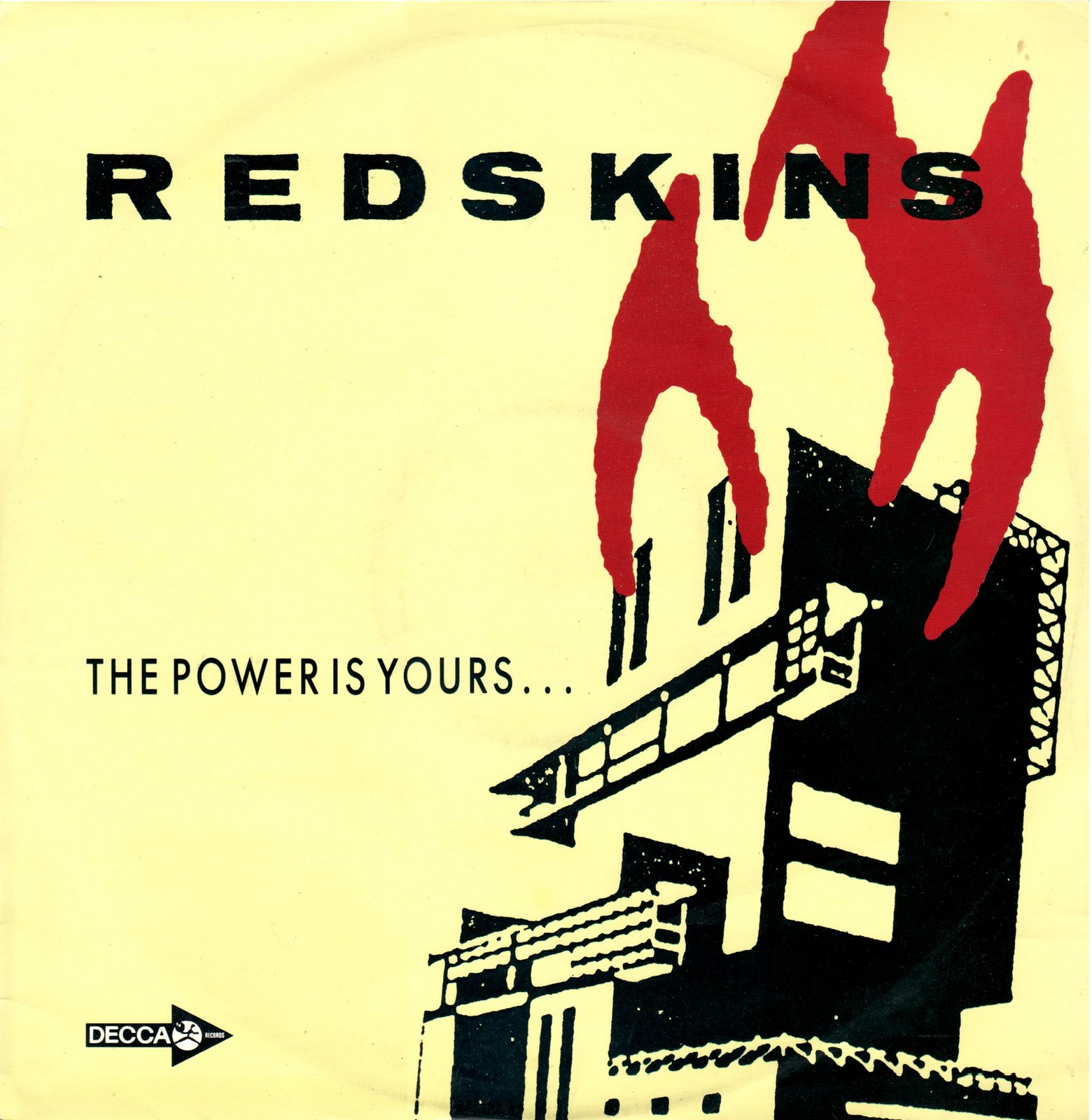

‘The Power Is Yours’ is a single I did for The Redskins. I used to do their label artwork. Chris Dean just controlled every aspect of the band, so he’d phone you up at night and talk to you about the typeface on the credit on the label, it was really like: ‘Chris, go to bed.’

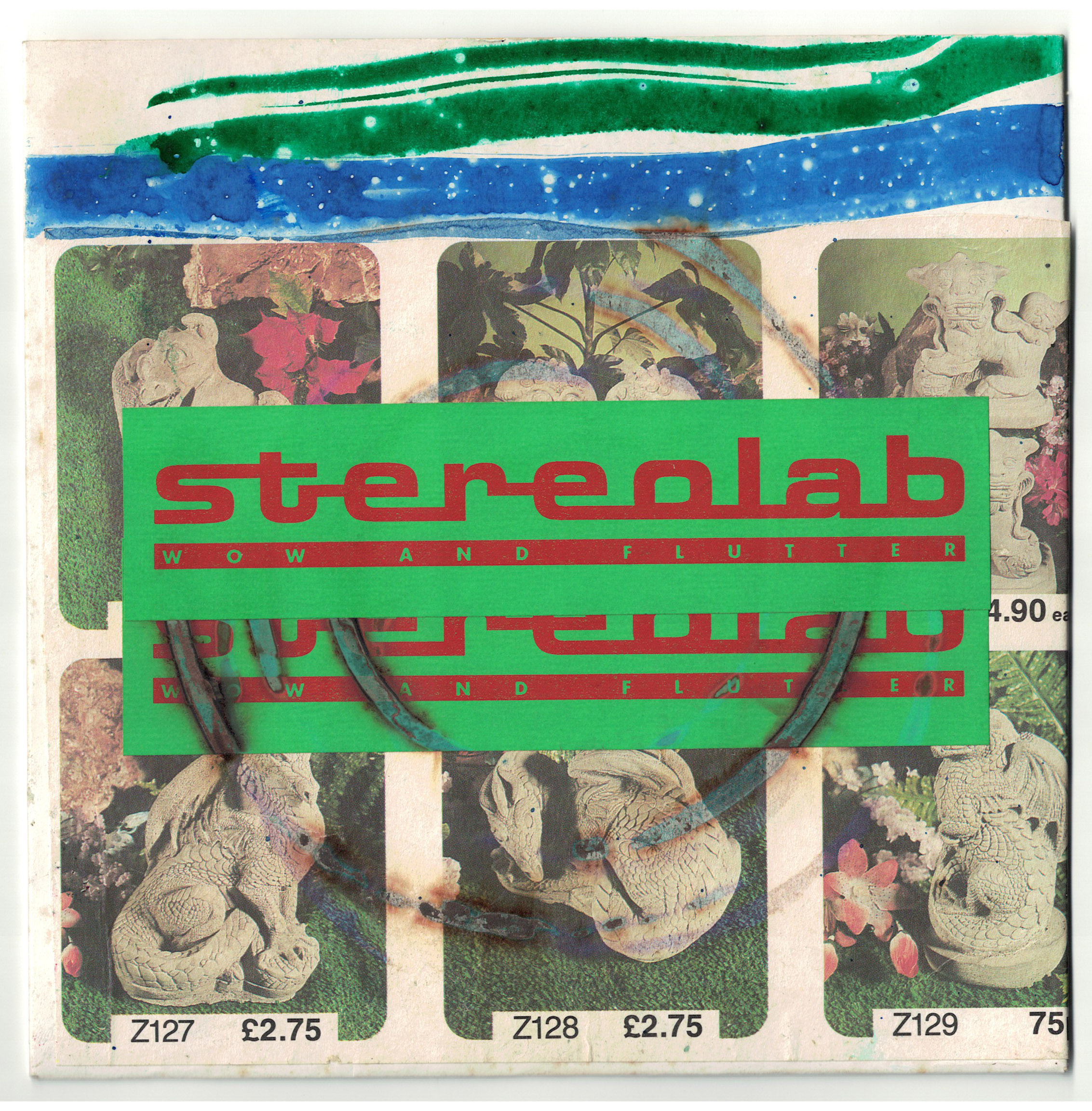

My career went on and on, I did little bits for Stereolab, I knew Tim [Gane] and Lætitia [Sadier] because they used to come up to the design studio I shared with Trouble, a loose collective with Andy ‘Hoople’ Holland and Dan Holliday who did a lot of their early stuff.

They did a single called ‘Wow and Flutter’, a 7”. There were three thousand of them, each sleeve was different and my role in that was I got the sleeves that had already got lots of collages on, and I put them on a Baby Belling’s hot ring, so anyone that’s got one with a spiral burn on it that was me. They’re another band that I always really wanted to get more involved with, I just love their stuff, and I was playing around with animation at the time and I really wanted to do some animation for them but it never happened.

I did some bits with Fila Brazilia, I did a film for them. I got involved with onedotzero which was a digital film festival at The ICA – I went all over Japan and Taiwan with that, doing Q&As – but one of the films I got commissioned to do by them was broadcast on the Channel 4 Animate programme, and led to a lot of animation work which I never really managed to capitalise on. I did a lot of work but it was a lot of work that wasn’t paying for itself, I was having to fund it with illustration work at the time, so it never took off.

Did that lead into you doing live tour visuals?

I was trying to stay away from live tour visuals, I wanted my stuff to be a bit more artistic than that, but that was the way it was going, anyone who wanted any motion graphics doing then it was for a wall in a bar or something, so I resisted that.

But you have done some quite high profile stuff, like you did The Rolling Stones’ tour.

Yeah, I did that, and I did an Oasis one for Glastonbury which was just awful …

You must have seen so many changes in design technology over the years.

Absolutely, that’s where we are. That’s why I’m enjoying paper and glue so much. That was the other thing, when I left the NME the key thing that happened in my career was that I bumped into the Apple Mac, and that’s what swerved me away very quickly from design into illustration, because it was nascent, you could only do dots, there was no smooth lines, and a dot matrix printer at 128K. I got given one from Apple, they were looking to throw them out into the creative community to see how that worked, and that was a really clever move from them because here we are, Apple Mac is the standard kit. Back then this little beige biscuit barrel arrived and it was just ‘well, what can this do?’ I found a way of doing illustration that was just mine, because no one else was doing it, so that was a really good wave to get onto.

How did you reconnect with Adrian, had you kept in touch with him over the years?

No. I bumped into him, again. Everytime I bump into him I get a bloody New Age Steppers sleeve to do, it’s a gift! I bumped into him in this little gallery I was involved with, DON’T WALK WALK gallery in Deal, Kent. I’ve got prints and artwork in there, and I was down there and the artist Jim Moir [Vic Reeves] was in there, and he went ‘Adrian! Adrian Sherwood!’ – and I wouldn’t have known, but I went over to him and he immediately gave me a big hug, it was amazing. I said ‘Adrian I did some work for you back in the day’, and the next thing I know I’m in the grip of this man. That was distinct from me following you on Instagram, because you posted the first album sleeve and I cheekily said ‘I designed that, I am Bill Bell’, I just thought it’s time I came out.

It was an amazing coincidence that, it was like we’d found Bill Bell. Because a lot of these people are completely missing, like Brady who designed the first single sleeeve, and legend has it suggested the label name.

That’s interesting, because on that collage, that last one [Avant Gardening Sleeve] I found this catalogue with old hi-fi stuff in it, and there’s this little unit, and it’s called not On-U Sound, but it’s something like On-Sound, and I’ve put a U in it for the artwork, but that is an actual product called that, and I wondered if that was where that name came from.

What was the process like of putting together the new sleeve for Avant Gardening, 40 years later?

When we first spoke about the project I immediately had a flood of ideas for how that might look. I was determined that I was going to design it, my elbow’s were out, that gig belonged to me. I’ve got a page of first sketches, they came out that first night after we agreed to do it, an amazing page of fast sketches, most of which have ended up on the actual album. But it was beautiful going back to look at how I used to work, and the disregard for copyright that I had, I was so free and young, because now I’d never dare to put Elvis Presley on anything.

I’d foolishly purged all my vinyl so didn’t even have a copy of the first album, so for the typography I had to go through all my fonts and think what it might have been. I have a draw of Letraset, so I went through them and I identified the fonts, because it was a different font on ‘The’ and a different font on ‘New Age Steppers’, so it was a labour of love. It was great actually because it was partly like a dream job where I’m back out there, on the slopes, by myself, the wind in my hair, and partly being art directed by you. It was the best of both worlds really, I like collaborative stuff, I knew that I had a firm hold on the imagery and the feel, then the rest … academic.

It’s a lovely companion piece to the original album.

It’s an updated, contemporary take on it. From my point of view, it was just a beautiful book ending of what’s been quite a long career, because to have that project right at the beginning of my career, and now, that is just so sweet.

Well it’s the 40th anniversary of the label this year, so to come back after 40 years and complete the circle is a beautiful thing.

New Age Steppers [1981] and Avant Gardening [2021] are available now on Vinyl directly from On-U Sound, alongside reissues of Action Battlefield [1982], Foundation Steppers [1983] and Love Forever [2012]

You can follow Andy Martin on Instagram and Twitter, where he regularly shares his many wonderful projects.

https://www.andymartin.gallery/